Acoustics

Studying architectural acoustics

Our approach to the archaeoacoustics study of Notre-Dame de Paris relies on acoustic measurements made in the cathedral before 2019. Replicating the inner geometry of the cathedral and calibrating this model to those measurements, the models are then modified based on available documentation to represent past or future architectural and decorative modifications. The simulations are then used to generate Room Impulse Responses (RIRs), which can be integrated into immersive, interactive rendering engines to reconstruct the acoustic conditions within the cathedral virtually [1].

When an acoustic source emits sound, the resulting sound that arrives at a listener/receiver position can be described as a combination of the initial, direct sound, and delayed reflections induced by obstacles (walls, etc.) between and around the source and receiver. The sum of those reflections over time constitutes the room's acoustic response. When the source stops producing, listeners perceive the gradual decay of sound as reverberation, i.e. the time it takes for the sound to fade. Therefore, the acoustical quality of a room depends on its reverberation time, which must be adapted to its use.

Scientists have been using physical and digital sound reconstruction methods for decades, but it is only recently that computer technologies have improved the quality and resolution of acoustic modelling sufficiently to enable them to tackle large-scale, complex spaces. With modern modelling approaches, sound in correctly simulated spaces can be perceptually comparable to actual on-site recordings. Once created, models can be modified to test acoustic conditions in different architectural configurations, source and listener positions, and usage contexts. Acoustic simulations can be a powerful tool for historical studies, providing researchers with a sensory presentation of sound previously available only through descriptions.

Digital acoustic twins

A digital twin can be described as a digital model of an intended or actual real-world physical system that serves as an effectively indistinguishable digital counterpart for practical purposes, such as simulation, testing, and evaluation. At the core of the current project is a digital acoustic twin of Notre-Dame de Paris Cathedral.

In architectural acoustics, numerical simulations have been used for years to analyse and predict the resulting acoustics in various buildings. With the evolving quality of numerical simulations, meticulous calibration, and the design of interactive and immersive systems employing the results of these models, it is now possible to provide indistinguishable virtual environments where the acoustics of a space — existing or not — can be examined through subjective evaluation and not just analytical metrics.

Model calibration

In historic auralizations, calibrating the studied building’s room acoustic simulation model is often necessary to accurately represent its acoustical environment. A methodical calibration procedure for GA models using room acoustics prediction programs to create realistic virtual audio realities, termed auralizations, has been proposed [2]. Perceptual evaluations of this method have also been carried out [3].

Architectural history of Notre-Dame

Developmental efforts commenced on the eastern extremity of the cathedral's ambulatory in 1163 while pre-existing church structures were demolished to clear the way. These structures included at least one large basilica underneath the modern forecourt. The inaugural construction phase concluded in 1182, after which a substantial retaining wall was built to allow services to occur inside the chancel while construction continued westward.

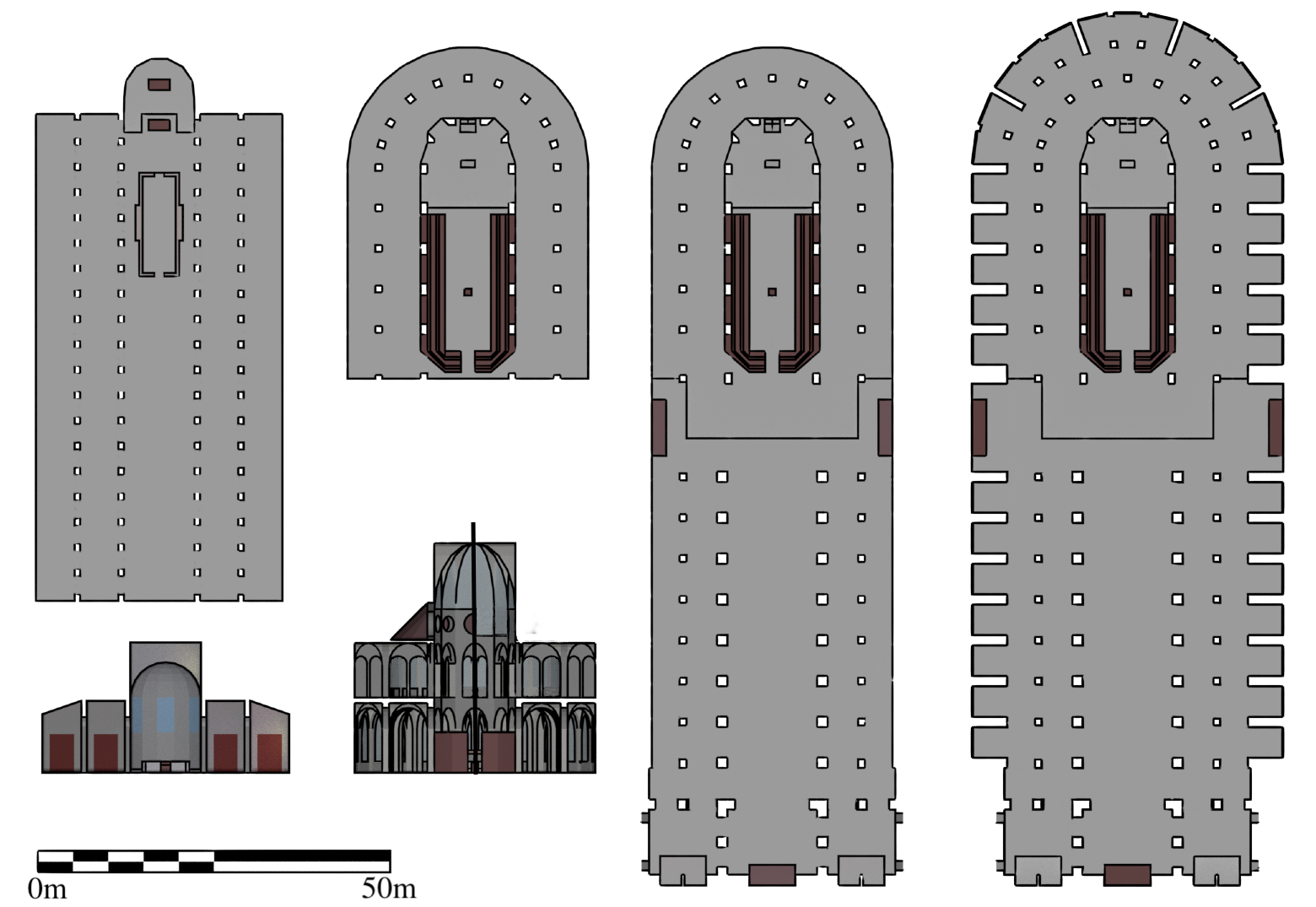

Acoustic model floor-plans and sections of cathedrals built on Île-de-la-Cité, from left to right: the pre-Gothic basilica underneath Notre-Dame's parvis (before 1163); Notre-Dame at its consecration (1182); completion of the nave (ca. 1220) and lateral chapels (ca. 1350).

Construction reached the grand facade by the 1220s, and subsequent development expanded the cathedral between the foundations of the flying buttresses, resulting in 35 lateral chapels. More details on the early acoustic conditions have been presented in [4] and [5]. After the 14th century, the external structure remained largely unchanged until the renovations of the 19th century.

Video: representation of the architectural history of Notre-Dame.

Characterising Acoustics

Several basic methods are commonly employed in room acoustic analysis. These are principally founded on exploitation of the transfer function associated with the effect of the room on an acoustic source for a given receiver. This transfer function is characterized by the RIR which can be measured or simulated in a variety of ways.

Reverberation Time: The reverberation time (Tx) is characterized by the decay rate of a sound, equated to the time it takes for the sound to decay by 60 dB (T60). Due to measurement dynamic constraints, RIR decay analysis is typically constrained to the decay from −5 dB to −25 dB (T20) or from −5 dB to −35 dB (T30), depending of the available dynamic range in the signal. Tx is always then projected to an equivalent time for T60. Reverberation time is then associated with the perceived decay at the end of a musical passage, as the sound decays into silence. The generally employed just noticeable difference (JND) for changes in reverberation time is 5%, for T60 > 1s.

Changing acoustics

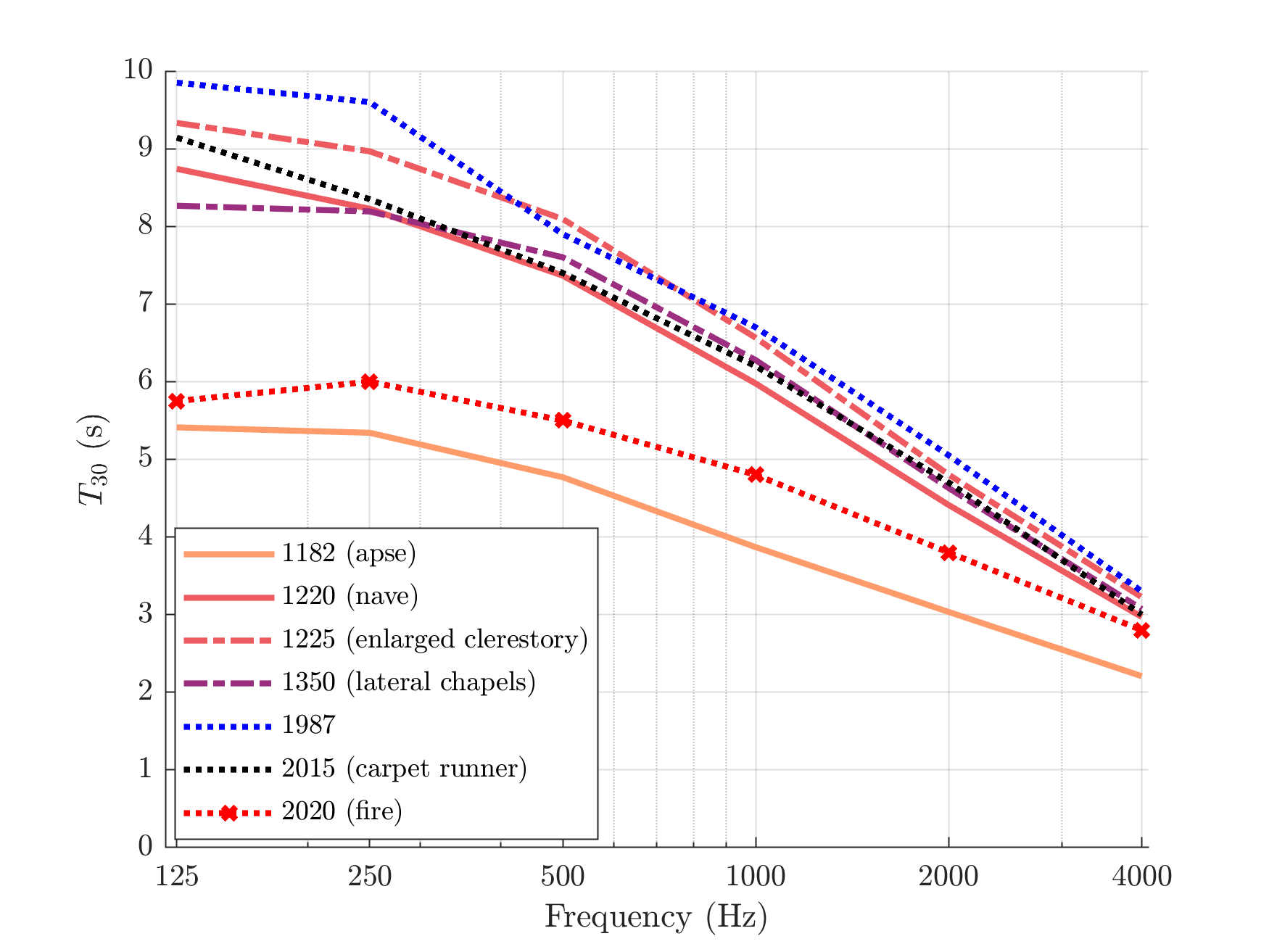

The figure below provides a summary of various reverberation times resulting from both geometrical acoustic simulations (typical decorative, unoccupied, prior to 1987) and measurements (from 1987 onwards) of Notre-Dame, as a result of various previous studies [3-6]. Of note is the 2020 (fire) condition, representing the post-fire measurements, with holes in the vaulted ceiling, and the 1182 (apse) condition, when only the Apse end of the cathedral was in open, which both have significantly shorter reverberation times than all other conditions, prior to the consideration of high festive decorations.

Collection of octave-band mean reverberation times in Notre-Dame following historically informed simulations (prior to 1987) and measurements (from 1987 onwards), unoccupied conditions (data from [3-6]).

Bibliography

[1] Katz, B. F.G., Murphy, D., and Farina, A., “The Past Has Ears (PHE) : XR Explorations of acoustic spaces as Cultural Heritage”, in Intl Conf on Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality and Computer Graphics (SALENTO AVR), volume 12243 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pp. 91–98, Salento, 2020, (url, video).

[2] Postma, B. N. and Katz, B. F.G., “Creation and Calibration Method of Virtual Acoustic Models for Historic Auralizations”, Virtual Reality, 19, pp. 161–180, 2015, (url).

[3] Postma, B. N. and Katz, B. F.G., “Perceptive and objective evaluation of calibrated room acoustic simulation auralizations”, J Acoust Soc Am, 140(6), pp.4326–4337, 2016, (url).

[4] Mullins, S. S., Canfield-Dafilou, E. K., and Katz, B. F.G., “The development of the early acoustics of the chancel in Notre-Dame de Paris: 1160-1230”, in Symp The Acoustics of Ancient Theatres, pp. 1–4, Verona, 2022, (url).

[5] Canfield-Dafilou, E. K., Mullins, S. S., and Katz, B. F.G., “Opening the lateral chapels and the acoustics of Notre-Dame de Paris: 1225-1330”, in Symp The Acoustics of Ancient Theatres, pp. 1–4, Verona, 2022, (url).

[6] Katz, B. F.G., and Weber, A., “An Acoustic Survey of the Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris before and after the Fire of 2019”, in Acoustics 2020, 2, 791–802; doi:10.3390/acoustics2040044, (url).