The Archaeology of Soundscapes

Introduction

The archaeology of soundscapes studies and analyses past sound environments to contribute to the re-creation of historical soundscapes. These reconstructions are working hypotheses, subject to modification based on new scientific data or interpretations. The UNESCO resolution on safeguarding intangible cultural heritage [1] emphasizes authenticity, which soundscape archaeology supports by offering plausible reconstructions while preserving authenticity.

Soundscapes are defined by the ISO standard as perceptual constructs existing through human perception. Audible models based on this definition allow sensory study of the past. By analysing archival traces and recordings, reconstructed soundscapes include real environmental sounds, not effects. Any irreproducible sounds due to data gaps are noted, but they do not detract from the immersive listening experience.

Soundscape archaeology recontextualizes history through sensory experiences, allowing us to explore monuments like Notre-Dame to understand their evolution, urban contexts, and social interactions. Major soundscape layers include:

- Geophony: Natural sounds (e.g., weather, location-specific sounds)

- Biophony: Sounds from fauna and flora (e.g., insects, birds)

- Anthropophony: Human-made sounds and their semiotic meaning

For more on this topic, see [2].

Evolution of the Geographical Space

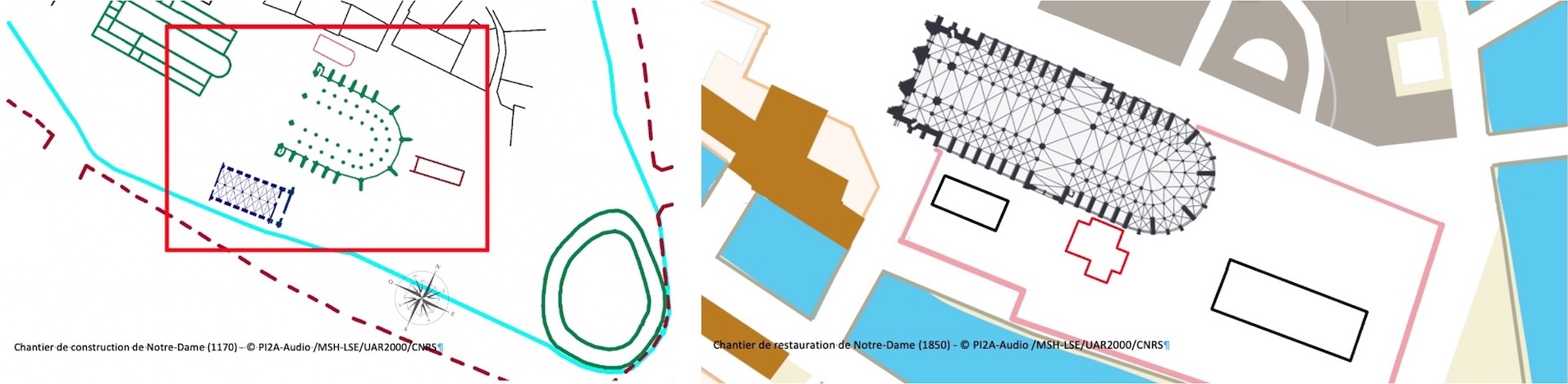

The geographical area around Notre-Dame evolved significantly between the 12th and 19th centuries. Changes included expansion of the site and urban construction and quay development. By 1850, the setting was closer to its contemporary appearance. However, transformations such as the mechanization of shipping (e.g. paddle-wheel boats) affected the acoustic environment.

Plan of the cathedral in 1170 and 1850, showing geographical and urban evolution.

Key Observations

Diachronic comparison highlights that technological advances, such as mechanized transport, introduced new sounds, that carpenters, masons, and blacksmiths played consistent roles in both periods, and that peripheral soundscapes (e.g., urban and river ambiences) underwent notable changes. Recreating historical soundscapes involves capturing and faithfully restoring these auditory elements. The process is documented in the research notebook ArcheoSon.

Case Study: Construction sites of the 12th and 19th centuries

Based on methodologies from projects like Bretez and ESPHAISTOSS, this project required the reconstruction of soundscapes of Notre-Dame's construction and restoration periods.

Soundscapes of 1170

During the medieval construction of Notre-Dame, social spaces included adults and children. Workers such as carpenters, stone cutters, masons, and blacksmiths dominated the environment. Carpenters erected scaffolding, while stone cutters worked on blocks and sculptures.

Soundscapes of 1850

During the 19th-century restoration under Viollet-le-Duc, the site was restricted to workers and craftsmen. Viollet-le-Duc aimed to faithfully restore the original structure, keeping activity sounds consistent with earlier periods.

Bibliography

[1] “Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage,” Technical report, UNESCO, 2018 (url).

[2] Katz, B. F.G. and Pardoen, M., “L’écho de la cathédrale,” in P. Dillmann, P. Liévaux, A. Magnien, and M. Regert, editors, Notre-Dame de Paris, la science à l'oeuvre, pp. 130–135, Le Cherche-Midi, 2022, ISBN 9782749174310. (url).